why don't some vultures have a syrinx?

welcome to A Teetering Vulture! a newsletter about various science stuff as well as the life happenings of its author, Taylor

(I’m finally writing a post about vultures! This is already my fifth month writing this newsletter, and it feels good and right that I’ve gotten around to talking about my favorite animals during my favorite month; both are a bit spooky and a bit focused on death, which is definitely part of what makes them both interesting and enjoyable, to me. With any luck, the contents of this post will make vultures more interesting to you as well, or will at least cast one part of their anatomy in an enigmatic light.)

A mystery I have been trying to solve recently is the reason vultures on this side of the globe don’t possess a syrinx, or voice box–the organ that allows almost all other birds to produce the panoply of vocalizations that fill the skies around the planet. The voice-producing organ in mammals is the larynx, which differs from the syrinx both in its location in the throat and in its structure, leading to vastly different sound-producing capabilities that preclude the complex warbles of songbirds and the hoots of owls. Nevertheless, I can’t think of a mammal nor a bird I encounter regularly that cannot communicate vocally, if need be. From herons to rabbits, the latter of which I very often see silently nibbling clover in my yard, and the former stock still and mute on a riverbank or edge of a pond, can respectively emit calls, or squeak and yell if sufficiently alarmed. The exception is the vulture. Despite living in the same environment as many loud creatures, it moves through its entire life in relative silence. And I wonder why.

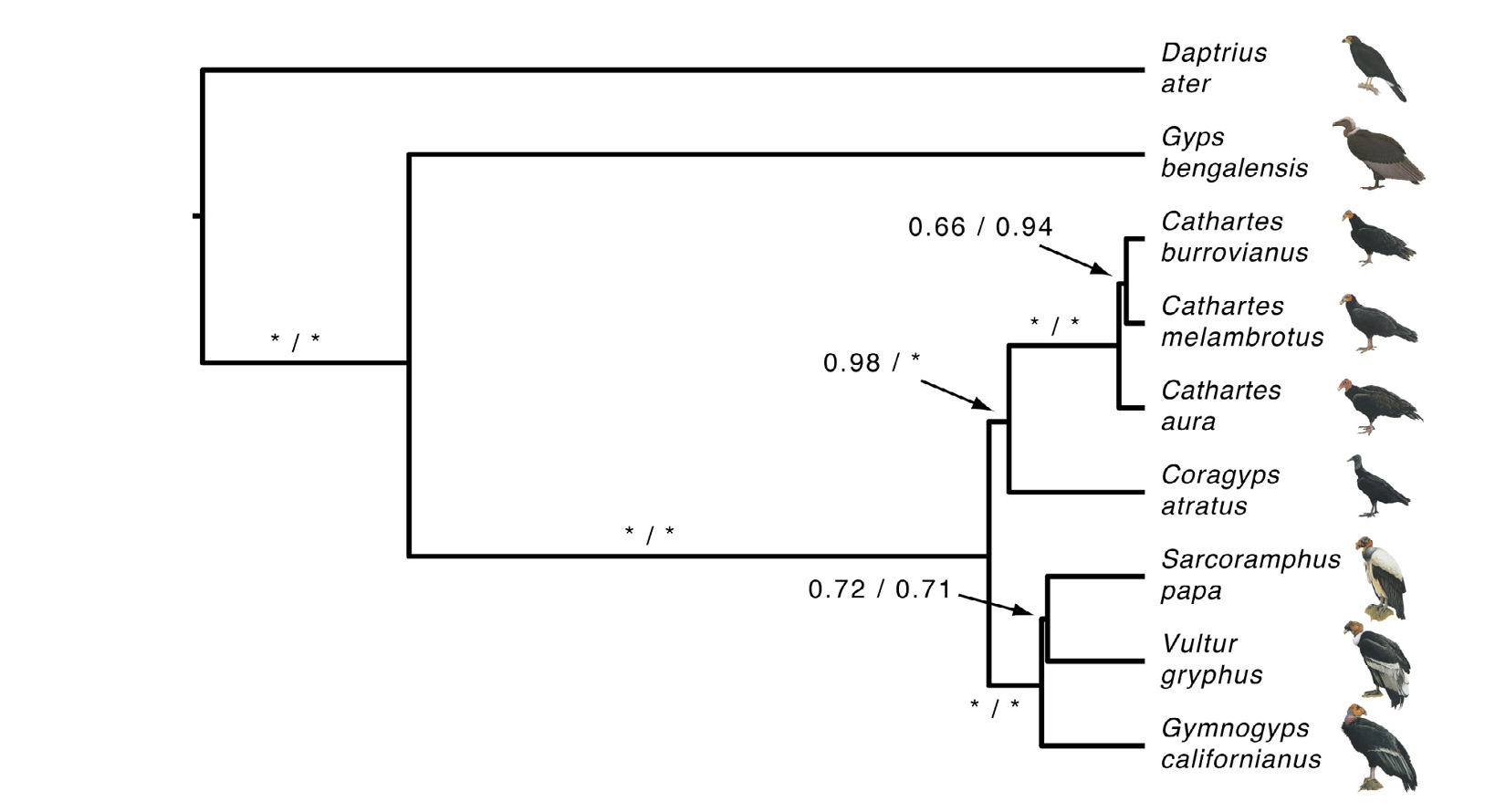

Vultures are commonly categorized as Old World vultures (that is, vultures of Eurasia, Africa, etc.) and New World vultures (vultures of North and South America), and each group isn’t actually that closely related to one another. New World vultures belong to the taxonomic family Cathartidae, which arose either in the Late Cretaceous (~69 million years ago) or Early Paleogene (~66 million years ago) and consists of the seven extant species of New World vulture around today, whereas the Old World Vultures have their own distinct lineage and belong to the family Accipitridae, which also includes birds of prey such as eagles and hawks. And the Old World vultures do have functioning syrinxes. Each group, New and Old World vultures, evolved to fill a particular role in their ecosystems–the general niche of large avian scavenger–but they did so separately, on their own. There did not exist one common ancestor of all vultures (unless, of course, you go back in history far enough to find an even more ancient ancester of all birds, perhaps the bird with the earliest version of the syrinx that has since been adapted to most bird species that exist today). Across ocean divides, the Old and New World vultures only happened to accrue many similar morphological traits because, well, the shape of a vulture is an ideal shape. To stick your face into carcasses for a living and spend the rest of your time scanning the skies for carcasses, a certain design is optimal. By which I mean: you gotta have a naked head and neck so you can keep yourself clean.

But although the convergent evolution of vultures means that outwardly a Eurasian Griffon Vulture and a California Condor look enough alike to group into one etymological family (the word vulture comes from the Latin vulturis, literally meaning vulture: a raptor that feeds on carrion and has a featherless neck and head), there are still many differences between the groups–only one of them being the New World vultures’ inability to do much more sonically than grunt and hiss. But that’s the one difference I’ve been interested in, of late.

Eurasian Griffon by The Urban Birder and California Condor by Brad Singer

I still haven’t found an answer. I mean, I have found an answer, it’s just one that is not totally satisfying. The answer to why any species is the way it is, is: it works well enough. Natural selection is the more official name for that answer, the biological term for ‘it works well enough.’ What is selected for, or what allows one organism to survive and impel its genetic material forth into a next generation, whether that be the presence or absence of certain traits, is always what works for an organism as it lives its life in a given environment, interacting with the components of that environment and shaping that environment with its existence.

So, essentially, being a grunty hissy vulture works because it works. Vultures have other ways of communicating that are unique to them, as well, from various gestures and flight patterns to feather ruffling. But, why doesn’t making vocalizations also work? Was it detrimental, at some point in time, for New World vultures to talk to one another like other birds talk to themselves? And so they lost their syrinx? Or was something else prioritized over the syrinx– something more important or more beneficial than any effects, positive or negative or neutral, of having a syrinx–so much so that the syrinx was done away with to make room for it?

When I was first considering possible ways to explain this, my mind went right away to diseases. Vultures live their lives encountering bacteria and other microorganisms that strike fear into the hearts of many people: Clostridium botulinum, the bacteria that produces the toxin that can result in botulism, for instance, or Bacillus anthracis, which causes the disease anthrax. Vultures have gastric acid and digestive environments that obliterate or nullify these organisms, or simply ensure they are expelled without causing harm–but what if an ancient syrinx couldn’t handle these and the myriad other nefarious byproducts of decay? What if ancient vultures perished because of complications to infected syrinxes? And so eventually the structure was, in a sense, abandoned?

Or maybe early New World vultures destroyed their syrinx themselves? Both turkey vultures and black vultures weaponize their stomach acid by projectile vomiting on threats. Maybe the syrinx wasn’t up to the task of withstanding this rather execrable defense mechanism.

Or was it a trade-off for a better sense of smell? Most birds have relatively small olfactory bulbs, a region of the brain connected to sense of smell. This includes Old World vultures, which rely primarily on their sense of sight to find their next meal. But turkey vultures have both the largest olfactory bulb relative to brain size of any bird species and a complex nasal cavity, and have been shown to rely on their sense of smell to navigate to food sources. Anatomically, was it not feasible for vultures to possess both a syrinx and large olfactory region of the brain? If that is the case, though, then why do black vultures and California condors not possess a similarly enhanced ability to smell? Why is the Andean condor adept at smelling, like the turkey vulture? All of these birds lack a syrinx, but their abilities to smell vary from very high to very low.

As I said, I still haven’t found an answer, or found anyone asserting a particular hypothesis as the most probable explanation. It’s not a mystery that’s been solved like other loss of anatomy mysteries have been solved–like humans losing their tails, for example, which has been correlated with our transition to bipedal creatures and has been connected to a specific genetic mutation. So–do I need to look through the genomes of vultures, to get my answer? Find which genes are associated with syrinx development? The turkey vulture species has had its genome sequenced, the code now stored in databases online. Gary Graves is one of the reasons for this; an ornithologist and the curator of birds at the Smithsonian, he was one of the co-organizers of the Birds 10,000 Genome Project, which is a project that aims to sequence the genomes of all extant bird species. He also happens to be interested in vultures. While studying the microbiomes of turkey vultures, he discovered an entire class of bacteria previously unknown to science that lives on their plumage, bacteria that are suited to the dry, often hot environments of vulture feathers. As their hosts spend hours soaring high in the sky, these microbes can contend perfectly fine with heat and high doses of radiation from the sun. Perhaps someone like this might already have the answer to my question, or have a better idea about how to go about finding an answer (or perhaps even have an idea of a more specific question to be asked).

For now though, it remains a puzzle I haven’t solved. I will update this post if I ever do figure it out, or if I simply get closer to figuring it out. Of course, if you have an answer–or an idea–that I haven’t considered (which is certainly possible), I’d be a little bit sad if you didn’t tell me. If that’s the case, I created this form where you can let me in on your knowledge. How convenient! The barrier between me and your knowledge is so low!

Information for this article was obtained from:

✼ Meet the Scientist Studying Vulture Guts for Clues to Disease Immunity ✼ Smithsonian Staff: Gary Graves ✼ Bird 10,000 Genomes Project ✼ Complexity of avian evolution revealed by family-level genomes ✼ Oxford English Dictionary: Vulture ✼ Multi-locus phylogenetic inference among New World Vultures (Aves: Cathartidae) ✼ Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Andean Condor Fact Sheet ✼ Anatomical evidence for scent guided foraging in the turkey vulture ✼ The microbiome of New World vultures ✼ Reddit: Is there an evolutionary purpose to vultures having no syrinx? ✼ Vomiting Black Vultures Take Over Couple's Florida Vacation Home: 'Smells Like a Thousand Rotting Corpses' ✼